Press

Signs from Broad Shoulders

Chicago possesses many admirable traits. Anthropomorphized by Carl Sandburg (or was it legendary Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg?) as the “City of Broad Shoulders,” the city offers nearly inexhaustible cultural diversions on par with New York City. However, the city pairs urbane tastes with an unassuming, Midwestern aura that makes it fertile ground for traditional craftsmanship.

Tony Janda has grown the Chicago-based Wooden Sign Co., which is located blocks from Wrigley Field, into a well-known company that caters to many of the Windy City’s bar owners and restaurateurs. Through decades of the sign business’s evolution, Janda’s dedication to fabrication remains unwavering.

An outside-the-box education

A Chicagoland native, Janda attended the Illinois Institute of Design, which offered a night-school program that emphasized design and commercial drafting, as well as the Chicago Art Institute. After completing his education in the early ’70s, Janda ventured west for an adventure and a sign-industry education. He spent a couple of weeks working in Charlie Hallenstein’s Orange County shop, which created signage and graphics for Disneyland and other, high-profile, West Coast attractions. During his travels, he noted graphic differences between the Left Coast and his hometown.

“Most signage in the Midwest, even in Chicago, incorporated a limited repertoire of styles and typesfaces – a little bit on the conservative side, I suppose,” he said. “The trip to California really opened my eyes to new artistic possibilities.”

In 1972, Janda, who’d recently married, opened a 1,100-sq.-ft. signshop that fabricated carved, sand¬blasted and gilded wood signage. Initially, he also screenprinted T-shirts, but decided to focus on dimensional signage.

“Blasting was a lot tougher back then because rubber masks weren’t available back then – duct tape was your only option,” Janda recalled. “Duct tape is much more difficult to remove from a surface because multiple layers were required to withstand the blast, and the adhesives were often very aggressive. I developed very strong hands.”

Wood you?

As his business thrived, Janda upgraded to a larger, approximately 5,000-sq.-ft. signshop that allowed a larger sandblasting booth and, later, a Graphtec cutting plotter to simplify patternmaking and prevent carpal-tunnel syndrome from “miles” of hand-cut vinyl.

Still a wood devotee, he frequently uses clear, vertical-grain redwood and Western red cedar for his sign faces. He also acknowledges HDU’s versatility for carved sculptures and sandblasted signage, and the shop has used it regularly to fabricate inte¬rior signs for approximately a decade. However, he maintains a consistent source of reclaimed redwood, cedar and mahogany, and, therefore, wood remains his primary substrate.

“In my opinion, HDU still doesn’t have a lot of history behind it,” Janda said. “It’s easy to carve and is pretty durable, but it doesn’t match wood’s strength across the board’s surface.”

Janda estimates approximately half his shop’s signs are sandblasted, while the remainder are carved, routed and sculpted. Currently, the shop has four employees that have worked together for more than 10 years. When the busy season arrives in spring – although Janda says there are rarely lulls except for the dead of winter – he’ll hire seasonal help to accommodate demand.

He said one of the major challenges of operating a signshop is finding the time to keep abreast of new equipment and materials, as well as following design trends. Janda also noted the competition that franchises and other quick-service signshops provide.

Changing clientele

During the early stages of his career, Janda’s customers walked into his shop with few concepts for their signage and granted him full artistic license. However, because clients have become increasingly knowledgeable about design and aware of their business’s goals, they often walk through the door with logos or renderings and a quick turnaround schedule.

His website, www.thewoodensignco.com, has yielded would-be customers from both coasts – once, even a sign-seeker from Japan. Occasionally, Janda will serve long-distance clients, but he prefers to stay local.

“Someone from out-of-state searching the Internet for signage is sometimes only interested in one thing – the price,” he said. “I enjoy working for customers who want signage that will set them apart and, ultimately, offer them a better investment. Fortunately, a good reputation due to quality work enables me to me stay in the shop and not have to pound the pave¬ment looking for clients.”

Chicago possesses many admirable traits. Anthropomorphized by Carl Sandburg (or was it legendary Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg?) as the “City of Broad Shoulders,” the city offers nearly inexhaustible cultural diversions on par with New York City. However, the city pairs urbane tastes with an unassuming, Midwestern aura that makes it fertile ground for traditional craftsmanship.

Tony Janda has grown the Chicago-based Wooden Sign Co., which is located blocks from Wrigley Field, into a well-known company that caters to many of the Windy City’s bar owners and restaurateurs. Through decades of the sign business’s evolution, Janda’s dedication to fabrication remains unwavering.

An outside-the-box education

A Chicagoland native, Janda attended the Illinois Institute of Design, which offered a night-school program that emphasized design and commercial drafting, as well as the Chicago Art Institute. After completing his education in the early ’70s, Janda ventured west for an adventure and a sign-industry education. He spent a couple of weeks working in Charlie Hallenstein’s Orange County shop, which created signage and graphics for Disneyland and other, high-profile, West Coast attractions. During his travels, he noted graphic differences between the Left Coast and his hometown.

“Most signage in the Midwest, even in Chicago, incorporated a limited repertoire of styles and typesfaces – a little bit on the conservative side, I suppose,” he said. “The trip to California really opened my eyes to new artistic possibilities.”

In 1972, Janda, who’d recently married, opened a 1,100-sq.-ft. signshop that fabricated carved, sand¬blasted and gilded wood signage. Initially, he also screenprinted T-shirts, but decided to focus on dimensional signage.

“Blasting was a lot tougher back then because rubber masks weren’t available back then – duct tape was your only option,” Janda recalled. “Duct tape is much more difficult to remove from a surface because multiple layers were required to withstand the blast, and the adhesives were often very aggressive. I developed very strong hands.”

Wood you?

As his business thrived, Janda upgraded to a larger, approximately 5,000-sq.-ft. signshop that allowed a larger sandblasting booth and, later, a Graphtec cutting plotter to simplify patternmaking and prevent carpal-tunnel syndrome from “miles” of hand-cut vinyl.

Still a wood devotee, he frequently uses clear, vertical-grain redwood and Western red cedar for his sign faces. He also acknowledges HDU’s versatility for carved sculptures and sandblasted signage, and the shop has used it regularly to fabricate inte¬rior signs for approximately a decade. However, he maintains a consistent source of reclaimed redwood, cedar and mahogany, and, therefore, wood remains his primary substrate.

“In my opinion, HDU still doesn’t have a lot of history behind it,” Janda said. “It’s easy to carve and is pretty durable, but it doesn’t match wood’s strength across the board’s surface.”

Janda estimates approximately half his shop’s signs are sandblasted, while the remainder are carved, routed and sculpted. Currently, the shop has four employees that have worked together for more than 10 years. When the busy season arrives in spring – although Janda says there are rarely lulls except for the dead of winter – he’ll hire seasonal help to accommodate demand.

He said one of the major challenges of operating a signshop is finding the time to keep abreast of new equipment and materials, as well as following design trends. Janda also noted the competition that franchises and other quick-service signshops provide.

Changing clientele

During the early stages of his career, Janda’s customers walked into his shop with few concepts for their signage and granted him full artistic license. However, because clients have become increasingly knowledgeable about design and aware of their business’s goals, they often walk through the door with logos or renderings and a quick turnaround schedule.

His website, www.thewoodensignco.com, has yielded would-be customers from both coasts – once, even a sign-seeker from Japan. Occasionally, Janda will serve long-distance clients, but he prefers to stay local.

“Someone from out-of-state searching the Internet for signage is sometimes only interested in one thing – the price,” he said. “I enjoy working for customers who want signage that will set them apart and, ultimately, offer them a better investment. Fortunately, a good reputation due to quality work enables me to me stay in the shop and not have to pound the pave¬ment looking for clients.”

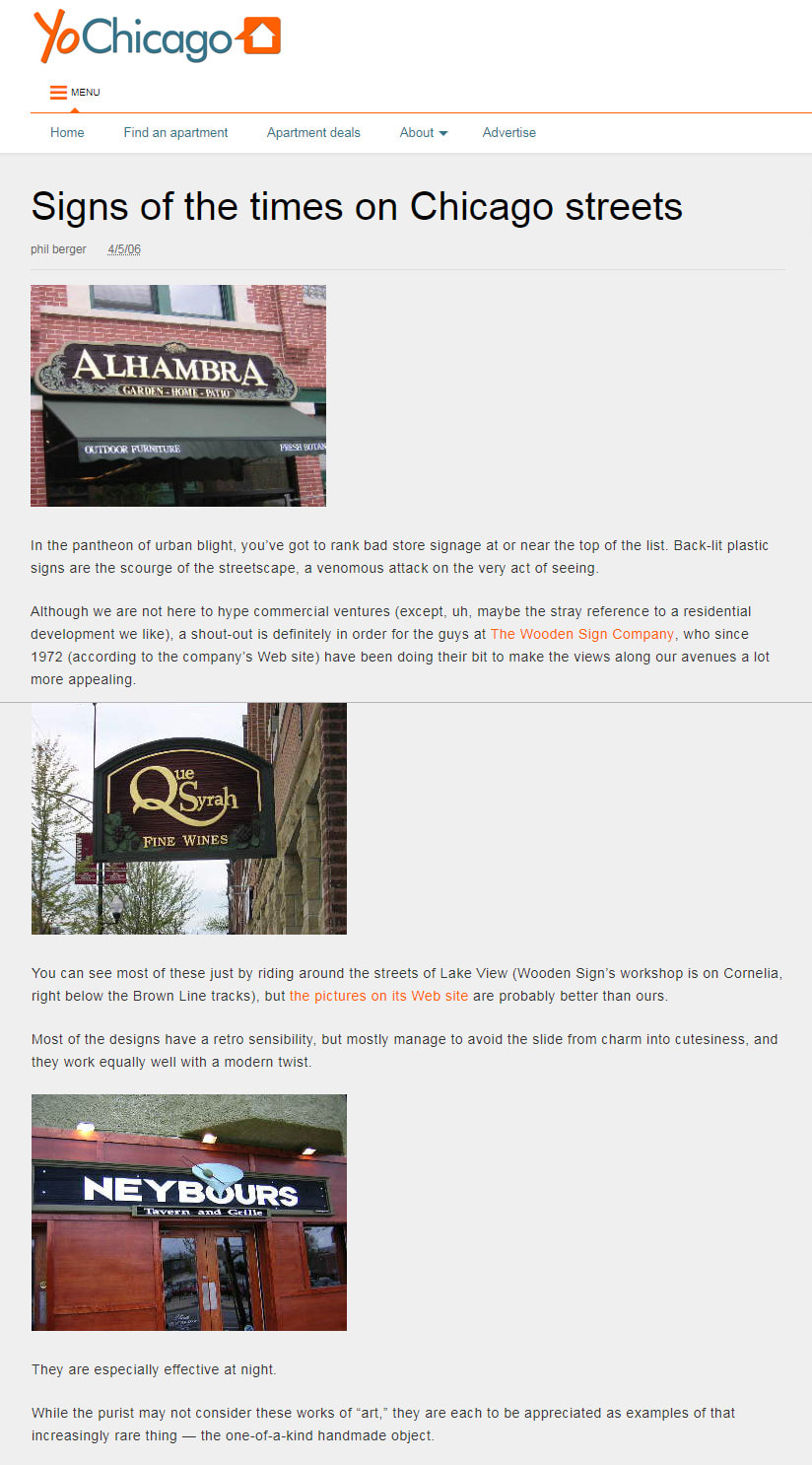

"In the pantheon of urban blight, you’ve got to rank bad store signage at or near the top of the list. Back-lit plastic signs are the scourge of the streetscape, a venomous attack on the very act of seeing.

Although we are not here to hype commercial ventures (except, uh, maybe the stray reference to a residential development we like), a shout-out is definitely in order for the guys at The Wooden Sign Company, who since 1972 (according to the company’s Web site) have been doing their bit to make the views along our avenues a lot more appealing.

You can see most of these just by riding around the streets of Lake View (Wooden Sign’s workshop is on Cornelia, right below the Brown Line tracks), but the pictures on its Web site are probably better than ours.

Most of the designs have a retro sensibility, but mostly manage to avoid the slide from charm into cutesiness, and they work equally well with a modern twist.

They are especially effective at night.

While the purist may not consider these works of “art,” they are each to be appreciated as examples of that increasingly rare thing — the one-of-a-kind handmade object."